In this lesson, we cover the Romanization of the Arabic abjad writing system to represent Arabic letters in any dialect using Latin script. In particular, we use the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC) Romanization standard.

Table of Contents

- ALA-LC Romanization Standard

- Arabic Letters

- Voiced vs. Voiceless Sounds

- Emphatic vs. Unemphatic Sounds

- “P,” “V,” and “G” Sounds in Arabic

- Different Shapes of Arabic Letters

- Arabic Letters that Only Connect to Preceding Letter

- لا (lām-’alif) Ligature in Arabic

- ى (’alif maqṣūrah)

- ة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘Tied-t’

- Level I – Beginner I (A1)

ALA-LC Romanization Standard

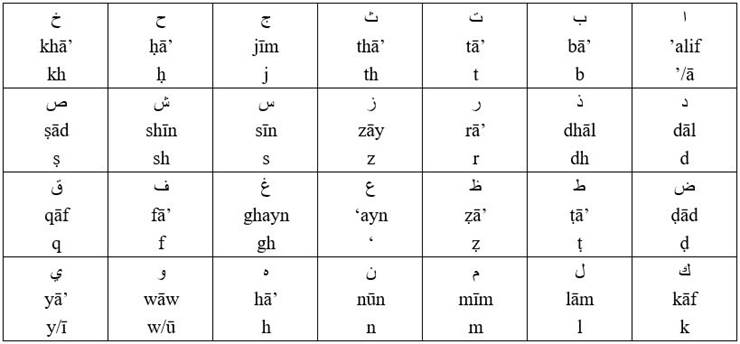

Arabic features sounds that can be challenging for speakers of Indo-European languages, such as English. This has led to adaptations of the Latin script to represent these unique sounds. One widely used romanization system was first published in 1991 by the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC) in 1991. This romanization system is also used by Wikipedia to represent Arabic text.

ALA-LC Arabic Romanization System used by Wikipedia

Arabic Letters

Arabic has 28 letters. It is written in a cursive script, meaning letters are joined together in a flowing manner within a word. Many letters also change shape depending on their position—standalone, initial, medial, or final. Here is a list of the Arabic letters written separately in a standalone position:

| Letter | Romanization | Name | Notes on Pronunciation |

| ا | ’ / ā | ’alif | At the beginning of a word or with ء (hamzah), e.g., أ, it sounds like a glottal stop, i.e., the sound at the beginning of “apple,” “egg,” “ox,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like a long “a” vowel, as in “cat,” “hat,” “sad,” etc. |

| ب | b | bā’ | Like “b” in “best,” “both,” “before,” etc. |

| ت | t | tā’ | Like “t” in “time,” “tank,” “ten,” etc. |

| ث | th | thā’ | Like “th” in “three,” “theta,” “thermal,” etc. |

| ج | j | jīm | Like “j” in “jar,” “job,” “joke,” etc. |

| ح | ḥ | ḥā’ | Like “h” in “home” but pronounced as a voiceless pharyngeal fricative in the throat. |

| خ | kh | khā’ | Like “ch” in German words, e.g., “Bach,” or Scottish words, e.g., “loch.” |

| د | d | dāl | Like “d” in “day,” “dark,” “dot,” etc. |

| ذ | dh | dhāl | Like “th” in “the,” “they,” “them,” etc. |

| ر | r | rā’ | Like a slightly trilled “r” in Spanish, by flapping the tongue once against the roof of the mouth. |

| ز | z | zāy | Like “z” in “zoo,” “zero,” “zone,” etc. |

| س | s | sīn | Like “s” in “sea,” “such,” “same,” etc. |

| ش | sh | shīn | Like “sh” in “show,” “shopping,” “short,” etc. |

| ص | ṣ | ṣād | An emphatic “s” sound. |

| ض | ḍ | ḍād | An emphatic “d” sound. |

| ط | ṭ | ṭā’ | An emphatic “t” sound. |

| ظ | ẓ | ẓā’ | An emphatic version of the “th” sound in “they.” |

| ع | ‘ | ‘ayn | A voiced pharyngeal fricative that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| غ | gh | ghayn | Like a French or German “r” pronounced at the back of the throat. |

| ف | f | fā’ | Like “f” in “first,” “family,” “find,” etc. |

| ق | q | qāf | A heavy and emphatic “k” sound. |

| ك | k | kāf | Like “k” in “key,” “kind,” “kitchen,” etc. |

| ل | l | lām | Like “l” in English but softer, similar to Spanish or French “l.” |

| م | m | mīm | Like “m” in “mark,” “master,” “mop,” etc. |

| ن | n | nūn | Like “n” in “now,” “north,” “nest,” etc. |

| ه | h | hā’ | Like “h” in “hat,” “horse,” “house,” etc. |

| و | w / ū | wāw | Like “w” in “world,” “work,” “want,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like “oo” in “food.” |

| ي | y / ī | yā’ | Like “y” in “yard,” “you,” “year,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like “ee” in “feed.” |

Pay attention to the transcription of ﺍ (’) and ع (‘), and notice the opposite direction of the two apostrophes.

Notice the following unfamiliar sounds to English speakers:

| Letter | Romanization | Name | Notes on Pronunciation |

| ح | ḥ | ḥā’ | Voiceless pharyngeal fricative, that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| خ | kh | khā’ | Voiceless velar fricative like “ch” in German words, e.g., “Bach,” or Scottish words “loch.” |

| ص | ṣ | ṣād | An emphatic “s” sound. |

| ض | ḍ | ḍād | An emphatic “d” sound. |

| ط | ṭ | ṭā’ | An emphatic “t” sound. |

| ظ | ẓ | ẓā’ | Like “th” sound in “they” but emphatic. |

| ع | ‘ | ‘ayn | Voiced pharyngeal fricative, that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| غ | gh | ghayn | Voiced velar fricative, like French “r” by rolling the back of the tongue against the velum (soft palate). |

| ق | q | qāf | A heavy and emphatic “k” sound. |

Romanization of the Arabic Abjad by the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC)

Voiced vs. Voiceless Sounds

Consider the following English sounds:

| Voiceless | Voiced |

| p | b |

| t | d |

| k | “g” as in “girl” |

| s | z |

| “th” as in “three” | “th” as in “they” |

| f | v |

Try to pronounce a voiceless consonant and the corresponding voiced counterpart. For example, compare the voiceless “f” and the voiced “v” by saying “ffff…” versus “vvvv….”

Notice that your tongue, teeth, and other articulators in your mouth remain in the same position. The only difference is the vibration of your vocal cords to produce the voiced sound.

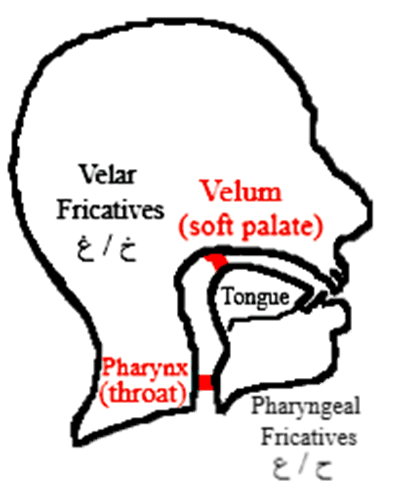

This applies to the letters خ (kh) and غ (gh), both of which are velar fricatives. Velar fricatives are articulated by the friction of the back of the tongue against the velum (soft palate). Whereas خ (kh) is voiceless, غ (gh) is voiced. Learning one sound can make it easier to produce the other. For example, if you can pronounce the German “ch” as in “Bach,” you can then try to consciously produce its voiced counterpart, غ (ghayn) ‘gh.’

| Voiceless | Voiced |

| ح ḥ | ع ‘ |

| خ kh | غ gh |

Similarly, the letters ح (ḥ) and ع (‘) are both pharyngeal fricatives, meaning they are articulated by creating friction in the pharynx, commonly known as the throat. Whereas ح (ḥ) is voiceless, ع (‘) is voiced. To pronounce ح (ḥ), try saying “h” as in “home,” but articulate it by creating friction in the throat.

Articulation of velar and pharyngeal fricatives

Emphatic vs. Unemphatic Sounds

In Arabic, there are four emphatic sounds, which may seem unfamiliar to English speakers. The four sounds and their corresponding unemphatic sounds are:

| Emphatic | Unemphatic |

| ص ṣ | س s |

| ض ḍ | د d |

| ط ṭ | ت t |

| ظ ẓ | ذ dh |

Try pronouncing the corresponding unemphatic sound while simultaneously withdrawing the tip of your tongue towards the roof of the mouth.

“P,” “V,” and “G” Sounds in Arabic

The sounds “p” as in “put,” “v” as in “voice,” and “g” as in “girl” do not exist in Standard Arabic. The letter ج (jīm) ‘j’ is pronounced like “j” in “jar.” However, in some dialects in Egypt, Yemen, and Oman, the letter ج (jīm) is pronounced like “g” in “girl,” i.e., ج (gīm) ‘g.’

The Arabic Abjad writing system is also used in Farsi, Urdu, Pashto, and Kurdish with some minor changes to include some sounds that do not exist in Arabic, such as “p,” “v,” and “g.”

It was also used to write the Turkish language during the Ottoman era, before the Latin alphabet was adopted by the Republic of Turkey in 1928.

Different Shapes of Arabic Letters

Arabic letters are cursive, changing their shape depending on their position: isolated, initial, medial, or final. Below is how Arabic letters appear based on their position:

| Isolated | Initial | Medial | Final |

| ا | ا | ـﺎ | ـﺎ |

| ب | بـ | ـبـ | ـب |

| ت | تـ | ـتـ | ـت |

| ث | ثـ | ـثـ | ـث |

| ج | جـ | ـجـ | ـج |

| ح | حـ | ـحـ | ـح |

| خ | خـ | ـخـ | ـخ |

| د | د | ـد | ـد |

| ذ | ذ | ـذ | ـذ |

| ر | ر | ـر | ـر |

| ز | ز | ـز | ـز |

| س | سـ | ـسـ | ـس |

| ش | شـ | ـشـ | ـش |

| ص | صـ | ـصـ | ـص |

| ض | ضـ | ـضـ | ـض |

| ط | طـ | ـطـ | ـط |

| ظ | ظـ | ـظـ | ـظ |

| ع | عـ | ـعـ | ـع |

| غ | غـ | ـغـ | ـغ |

| ف | فـ | ـفـ | ـف |

| ق | قـ | ـقـ | ـق |

| ك | كـ | ـكـ | ـك |

| ل | لـ | ـلـ | ـل |

| م | مـ | ـمـ | ـم |

| ن | نـ | ـنـ | ـن |

| ه | هـ | ـهـ | ـه |

| و | ـو | ـو | ـو |

| ي | يـ | ـيـ | ـي |

Arabic Letters that Only Connect to Preceding Letter

Note that the following letters only connect to the preceding letter and not to the subsequent letter:

| Isolated | Initial | Medial or Final |

| ا | ا | ـﺎ |

| د | د | ــد |

| ذ | ذ | ــذ |

| ر | ر | ــر |

| ز | ز | ــز |

| و | و | ــو |

لا (lām-’alif) Ligature in Arabic

In writing, the combination of the letter ل (lām) ‘l’ followed by ﺍ (’alif) is written using the mandatory ligature ﻻ, with variations depending on the font. Below is how this ligature appears in writing based on its position in the word:

| Isolated | Initial | Medial | Final |

| ﻻ | ﻻ | ـﻼ | ـﻼ |

ى (’alif maqṣūrah)

The ى (’alif maqṣūrah), which is written as a dotless ي (yā’) ‘y,’ is a special form of the letter ﺍ (’alif) that can appear only at the end of a word. If a word in Arabic ends with the long vowel ā, pronounced like “a” in “cat,” it can be written with either an ﺍ (’alif) or ى (’alif maqṣūrah) based on some specific rules.

This is an advanced topic for this level, so we will touch on it only briefly. Feel free to skip this part for now. The key point is that ى can only appear at the end of a word and is pronounced like an ﺍ (’alif) representing the long vowel ā.

There are two common cases where the ى (’alif maqṣūrah) is used:

1. Some proper names, such as:

| Masculine Proper Names | Feminine Proper Names |

| مـوســى (mūsā) ‘Moses’ | لَـيْـلــى (laylā) ‘Layla’ |

| عِـيـســى (‘īsā) ‘Jesus’ | سَـلْـمــى (salmā) ‘Salma’ |

| يَـحْـيــى (yaḥyā) ‘John’ | مُـنــى (munā) ‘Muna’ |

2. Verbs in the third-person singular masculine past tense whose third-person singular masculine present tense ends in ي (yā’) ‘y.’ Here are some examples for reference:

| 3rd-person sing. masc. present | 3rd-person sing. masc. past |

| بِــــرْمِــــيْ (birmī) ‘he throws’ | رَمــى (ramā) ‘he threw’ |

| بِــشْـــتِـــرِيْ (bishtarī) ‘he buys’ | اِشْــتَـرى (ishtarā) ‘he bought’ |

| بِــــبْــــنِــــيْ (bibnī) ‘he builds’ | بَـــنَـــى (banā) ‘he built’ |

ة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘Tied-t’

When the letter ت (tā’) ‘t’ appears at the end of a word, it can take one of two forms:

- ت : also called تـاء مَـفْـتـوحَـة (tā’ maftūḥah) ‘open-t’

- ة : also called تـاء مَـرْبـوطَـة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘tied-t’

The ة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘tied-t’ is often used as a gender marker for the feminine form of a noun or adjective, though there are exceptions. Further details will be covered in Level II, Lesson 2.

In MSA, if a word ends with ة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘tied-t,’ it is pronounced as “h” when it is the last letter in a phrase or sentence. Otherwise, ة (tā’ marbūṭah) is pronounced as “t.”

| ة pronounced as “h” | ة pronounced as “t” |

| كُـــــرَة kurah ball | كُـــــرَة الـــقَــــدَم kurat al-qadam football |

| مَـــديــنَـــة madīnah city | مَـــديــنَـــة الــقــــاهِــــرَة madīnat al-qahirah Cairo City |

Note that the ة (tā’ marbūṭah) ‘tied-t’ is always preceded by a ‘short a’ or ‘long ā’ vowel in MSA.

| Have you ever wondered why Indo-European languages have the letter “Q” in their alphabet? It seems that “K” and “C” do the job just fine. Well, the letter “Q” came from Greek “Ϙ” (Koppa), derived from the Phoenician “ϕ” (qoph), a sound corresponding to Arabic ق (qāf). Both Phoenician and Arabic are Semitic languages. |

Next: Linguistic Features of Palestinian-Jordanian Arabic

Other lessons in Level I: