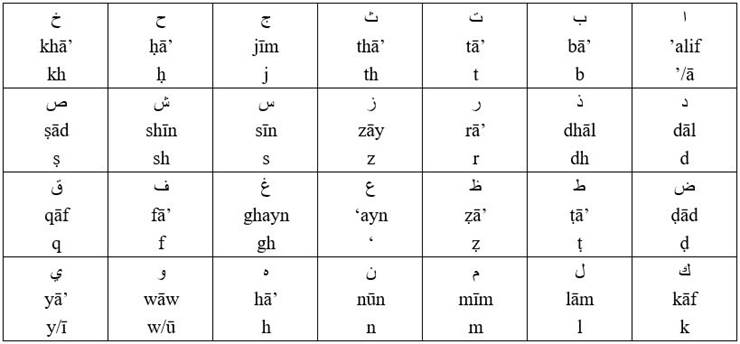

In this lesson, we cover the Romanization of the Arabic abjad writing system to represent Arabic letters using Latin script. In particular, we use the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC) Romanization standard.

ALA-LC Romanization Standard

Arabic features some sounds that are challenging to pronounce for speakers of Indo-European languages, such as English. This requires adaptation of the Latin script to represent these unique sounds. One common romanization system was first published by the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC) in 1991. This is the romanization system used by Wikipedia, for example, to represent Arabic writing.

ALA-LC Arabic Romanization System used by Wikipedia

Arabic Letters

There are 28 letters in Arabic. Remember that Arabic writing is cursive, which means that letters are joined in a flowing manner in the same word. In other words, some letters change shape depending on their position in the word, i.e., standalone, initial, medial, and end. Here is a list of the Arabic letters written separately in a standalone position:

| Letter | Romanization | Name | Notes on Pronunciation |

| ا | ’/ā | ’alif | At the beginning of a word or with ء (hamzah), e.g., أ, it sounds like a glottal stop, i.e., the sound at the beginning of “apple,” “egg,” “ox,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like a long “a” vowel, as in “cat,” “hat,” “sad,” etc. |

| ب | b | bā’ | Like “b” in “best,” “both,” “before,” etc. |

| ت | t | tā’ | Like “t” in “time,” “tank,” “ten,” etc. |

| ث | th | thā’ | Like “th” in “three,” “theta,” “thermal,” etc. |

| ج | j | jīm | Like “j” in “jar,” “job,” “joke,” etc. |

| ح | ḥ | ḥā’ | Like “h” in “home” but articulated by creating friction in the throat. |

| خ | kh | khā’ | Like “ch” in German words, e.g., “Bach,” or Scottish words, e.g., “loch.” |

| د | d | dāl | Like “d” in “day,” “dark,” “dot,” etc. |

| ذ | dh | dhāl | Like “th” in “the,” “they,” “them,” etc. |

| ر | r | rā’ | Like a slightly trilled “r” in Spanish, by flapping the tongue once against the roof of the mouth. |

| ز | z | zāy | Like “z” in “zoo,” “zero,” “zone,” etc. |

| س | s | sīn | Like “s” in “sea,” “such,” “same,” etc. |

| ش | sh | shīn | Like “sh” in “show,” “shopping,” “short,” etc. |

| ص | ṣ | ṣād | An emphatic “s” sound. |

| ض | ḍ | ḍād | An emphatic “d” sound. |

| ط | ṭ | ṭā’ | An emphatic “t” sound. |

| ظ | ẓ | ẓā’ | Like “th” sound in “they” but emphatic. |

| ع | ‘ * | ‘ayn | Voiced pharyngeal fricative that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| غ | gh | ghayn | Like a French “r” rolled using the back of the tongue against the soft palate. |

| ف | f | fā’ | Like “f” in “first,” “family,” “find,” etc. |

| ق | q | qāf | A heavy and emphatic “k” sound. |

| ك | k | kāf | Like “k” in “key,” “kind,” “kitchen,” etc. |

| ل | l | lām | Like “l” in English but softer, similar to Spanish or French “l.” |

| م | m | mīm | Like “m” in “mark,” “master,” “mop,” etc. |

| ن | n | nūn | Like “n” in “now,” “north,” “nest,” etc. |

| ه | h | hā’ | Like “h” in “hat,” “horse,” “house,” etc. |

| و | w/ū | wāw | Like “w” in “world,” “work,” “want,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like “oo” in “food.” |

| ي | y/ī | yā’ | Like “y” in “yard,” “you,” “year,” etc. When used as a vowel, it sounds like “ee” in “feed.” |

* Pay attention to the transcription of ﺍ (’) and ع (‘), and notice the opposite direction of the two apostrophes.

| An older order of the Arabic alphabet, called abjad order, was used before the 8th century CE. This order is in line with the order used by other Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic: ا ب ج د ه و ز ح ط ي ك ل م ن س ع ف ص ق ر ش ت ث خ ذ ض ظ غ and is often recited as: أَبْـجَـدْ هَـوَّزْ حُـطّـي كَـلَـمَـنْ سَـعْـفَـصْ قُـرِشَـتْ ثَـخَـذٌ ضَـظَـغٌ (’abjad hawwaz ḥuṭṭī kalaman sa‘faṣ qurishat thakhadhun ḍaẓaghun) The current order, also known as hijā’ī order, was adopted to bring similar letters in sequence: ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي |

Notice the following unfamiliar sounds to English speakers:

| Letter | Romanization | Name | Notes on Pronunciation |

| ح | ḥ | ḥā’ | Voiceless pharyngeal fricative, that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| خ | kh | khā’ | Voiceless velar fricativelike “ch” in German words, e.g., “Bach,” or Scottish words “loch.” |

| ص | ṣ | ṣād | An emphatic “s” sound. |

| ض | ḍ | ḍād | An emphatic “d” sound. |

| ط | ṭ | ṭā’ | An emphatic “t” sound. |

| ظ | ẓ | ẓā’ | Like “th” sound in “they” but emphatic. |

| ع | ‘ | ‘ayn | Voiced pharyngeal fricative, that is unique to Semitic languages. |

| غ | gh | ghayn | Voiced velar fricative, like French “r” by rolling the back of the tongue against the velum (soft palate). |

| ق | q | qāf | A heavy and emphatic “k” sound. |

Romanization of the Arabic Abjad by the American Library Association and the Library of Congress (ALA-LC)

Voiced vs. Voiceless Sounds

Consider the following English sounds:

| Voiceless | Voiced |

| p | b |

| t | d |

| k | g as in “girl” |

| s | z |

| “th” as in “three” | “th” as in “they” |

| f | v |

Try to pronounce a voiceless consonant and the corresponding voiced counterpart. For example, compare the voiceless “f” and the voiced “v” by saying “ffff…” versus “vvvv….”

Notice that your tongue, teeth, and other articulators in your mouth remain in the same position. The only difference is the vibration of your vocal cords to produce the voiced sound.

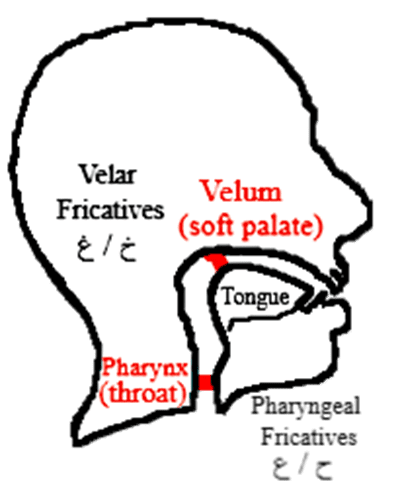

This applies to the letters خ (kh) and غ (gh), both of which are velar fricatives. Velar fricatives are articulated by the friction of the back of the tongue against the velum (soft palate). Whereas خ (kh) is voiceless, غ (gh) is voiced. Learning one sound can make it easier to produce the other. For example, if you can pronounce the German “ch” as in “Bach,” you can then try to consciously produce its voiced counterpart, غ (ghayn) ‘gh.’

| Voiceless | Voiced |

| ح ḥ | ع ‘ |

| خ kh | غ gh |

Similarly, the letters ح (ḥ) and ع (‘) are both pharyngeal fricatives, meaning they are articulated by creating friction in the pharynx, commonly known as the throat. Whereas ح (ḥ) is voiceless, ع (‘) is voiced. To pronounce ح (ḥ), try saying “h” as in “home,” but articulate it by creating friction in the throat.

Articulation of velar and pharyngeal fricatives

Emphatic vs. Unemphatic Sounds

In Arabic, there are four emphatic sounds, which may seem unfamiliar to English speakers. The four sounds and their corresponding unemphatic sounds are:

| Emphatic | Unemphatic |

| ص ṣ | س s |

| ض ḍ | د d |

| ط ṭ | ت t |

| ظ ẓ | ذ dh |

Try pronouncing the corresponding unemphatic sound while simultaneously withdrawing the tip of your tongue towards the roof of the mouth.

“P,” “V,” and “G” Sounds in Arabic

The sounds “p” as in “put,” “v” as in “voice,” and “g” as in “girl” do not exist in Standard Arabic. The letter ج (jīm) ‘j’ is pronounced like “j” in “jar.” However, in some dialects in Egypt, Yemen, and Oman, the letter ج (jīm) is pronounced like “g” in “girl,” i.e., ج (gīm) ‘g.’

The Arabic Abjad writing system is also used in Farsi, Urdu, Pashto, and Kurdish with some minor changes to include some sounds that do not exist in Arabic, such as “p,” “v,” and “g.”

It was also used to write the Turkish language during the Ottoman era, before the Latin alphabet was adopted by the Republic of Turkey in 1928.

| Have you ever wondered why Indo-European languages have the letter “Q” in their alphabet? It seems that “K” and “C” do the job just fine. Well, the letter “Q” came from Greek “Ϙ” (Koppa), derived from the Phoenician “ϕ” (qoph), a sound corresponding to Arabic ق (qāf). Both Phoenician and Arabic are Semitic languages. |

Next: Cursive Features of Arabic Letters

Other lessons in Level I: